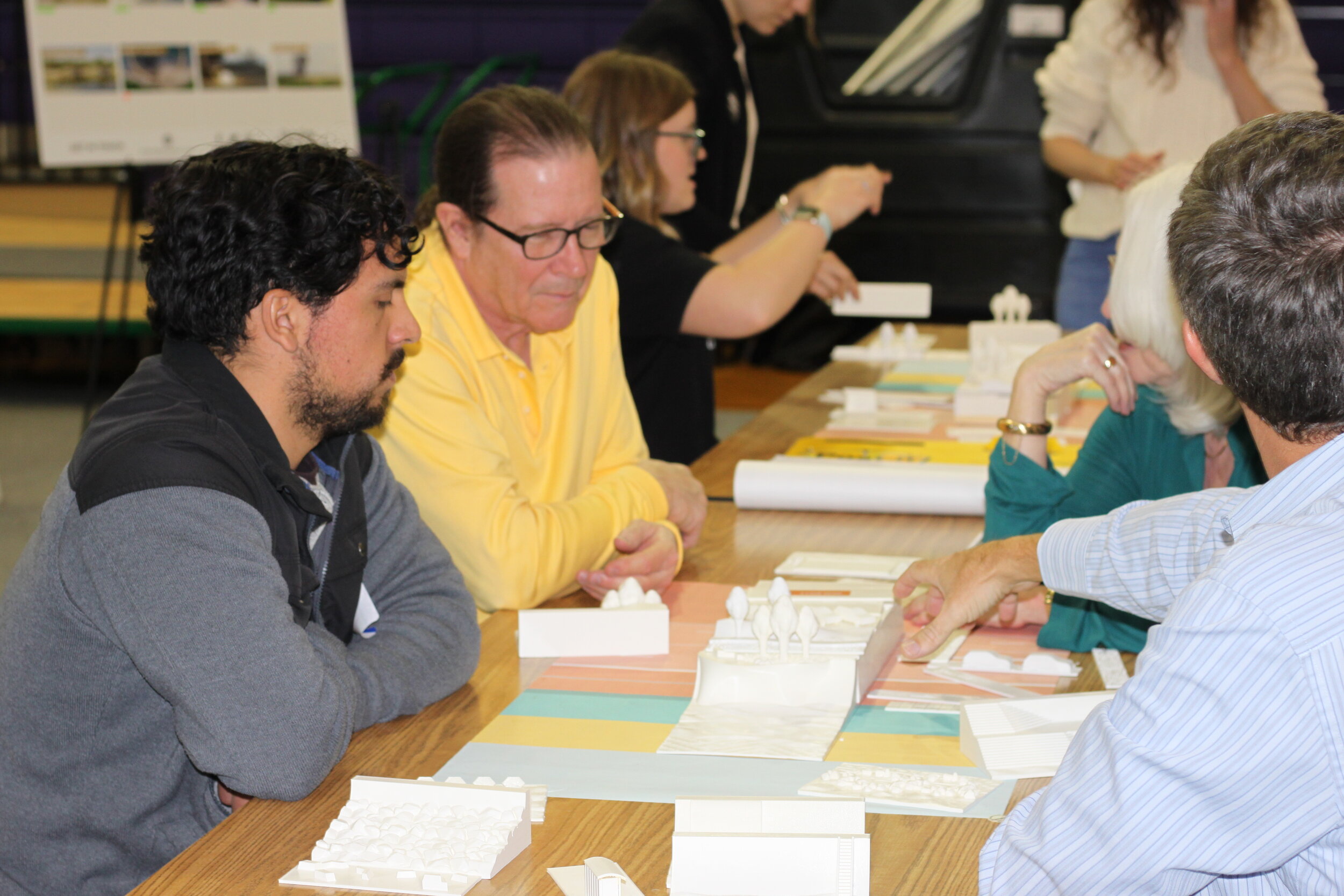

Building teams is of course inherent in the process of designing and constructing landscapes; we routinely partner with engineers along with experts in ecology, soils, irrigation and lighting. But as the scale, the complexity, and the ambition (climate change, social and racial equity, environmental justice) of the projects we are asked to address grows, our teams have amplified, especially when you include stakeholders and clients in the mix. Elaborate and tangled, large teams can become unwieldy quickly, seriously undermining a project’s success. But, collaboration is critical, the underlying goal (and reward) is the ability to draw on team member’s professional and life experiences, to allow for a mix of ideas and perspectives that will inform a project in interesting ways.

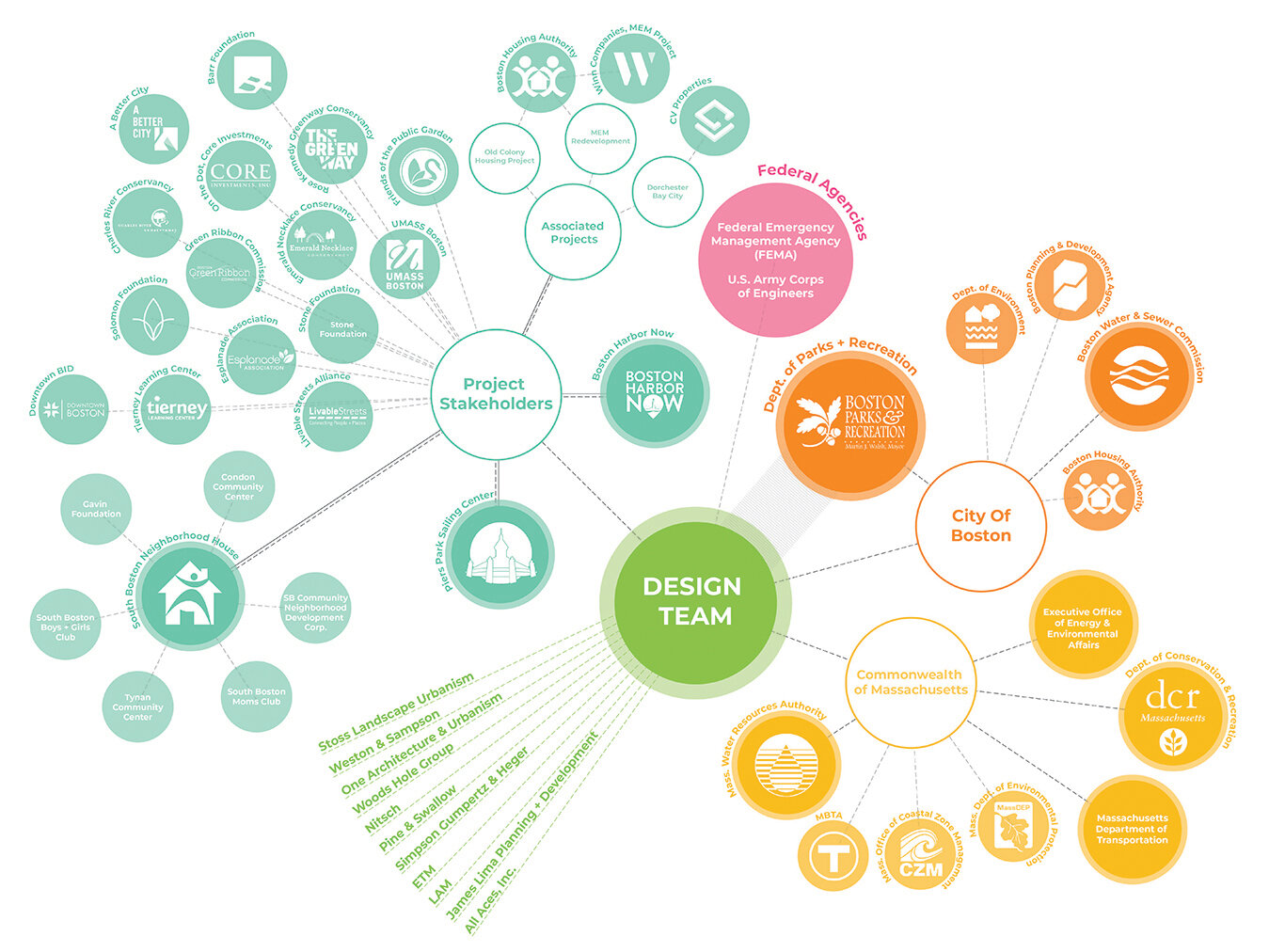

A quick glance at the project team graphic above underscores how incredibly important it is to be deliberate about the collaborative process. After leading two very large teams in the past few years, Moakley Park and the Brickline Greenway, we have learned (sometimes the hard way) the fundamentals critical in the process of building and managing teams. And, while we often talk about this internally, sharing our learnings helps us all be better partners. When we approach collaboration we believe there are four components to consider; behavior, structure, process, and communication.

Behavior

Underpinning all great collaboration is trust. Of course trust is built-in (hopefully) when you team with people/firms with whom you have a positive shared history. To that end, cultivating good relationships pays dividends; you get a head start when adding ‘heritage relationships’ to your team and we do this 50-60% of the time. But building new relationships is the lifeblood to any practice, providing opportunities for learning and growth. Here, there are a couple of essentials that must be practiced, fostered and institutionalized… respect, adaptability, and organization. Conflict is inevitable on large projects and without these three ingredients successful collaboration is impossible.

Structure

When we speak of structure, we think about setting a solid foundation. Firstly, we look for diversity within our teams to ensure that many voices and perspectives are represented. We think this difference makes for better collaboration. But at the same time, we look for common ground, partners and even clients with shared values, goals and expectations for the project as well as alignment on levels of commitment and motivation.

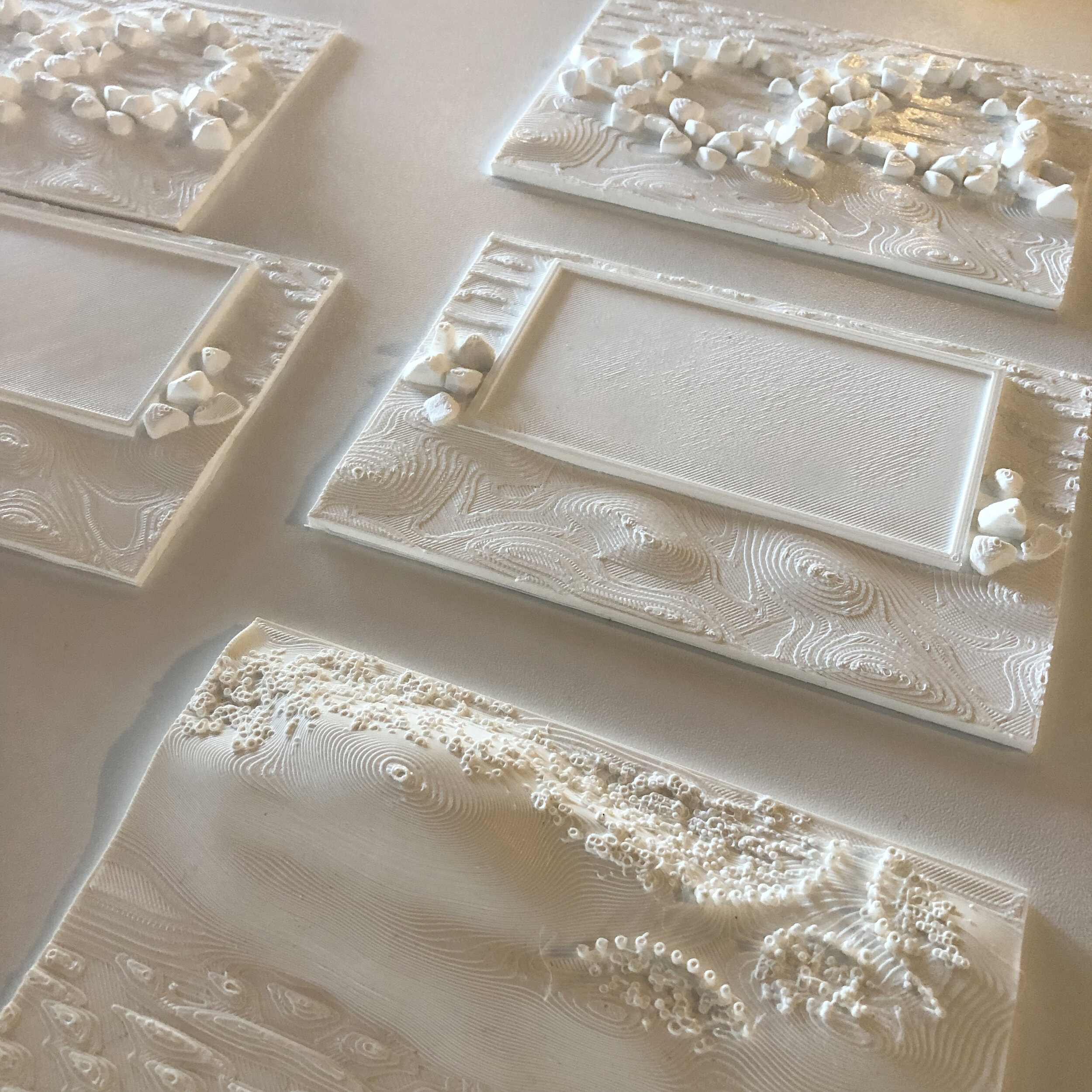

Process

As important as developing a process for collaboration, is articulating it to the entire team. Processes for collaboration, communication, and conflict resolution are essential and must be clearly established at the outset of any multi-partner project. In addition, we work hard to eliminate ambiguity and ensure that everyone has clear roles and lines of responsibility and that members' strengths and capabilities are clearly defined and complimentary. Organizational charts and diagrammatic maps provide visibility and clarity to the team as do clear and precise protocols and detailed schedules and expectations for collaboration. The upfront work of providing detailed governance for a project team pays off over the course of a complex project.

Communication

Orchestrating the flow of knowledge is imperative. While transparency and keeping everyone ‘in the loop’ is essential, it’s also important to make sure that communication is efficient and productive. When we think of communication we look at how it is organized, integrated, filtered and condensed–an overload of unorganized communication is as detrimental as too little communication. Meeting notes that are precise, easy to digest, and actionable are essential along with investing in tools for real-time collaboration like Slack, Miro or even Google Docs. Mindful communication facilitates flow, eliminates barriers, and is action oriented. Lastly, there must be a culture of knowledge integration where everyone is willing, able and encouraged to share knowledge – this goes full circle back to trust.

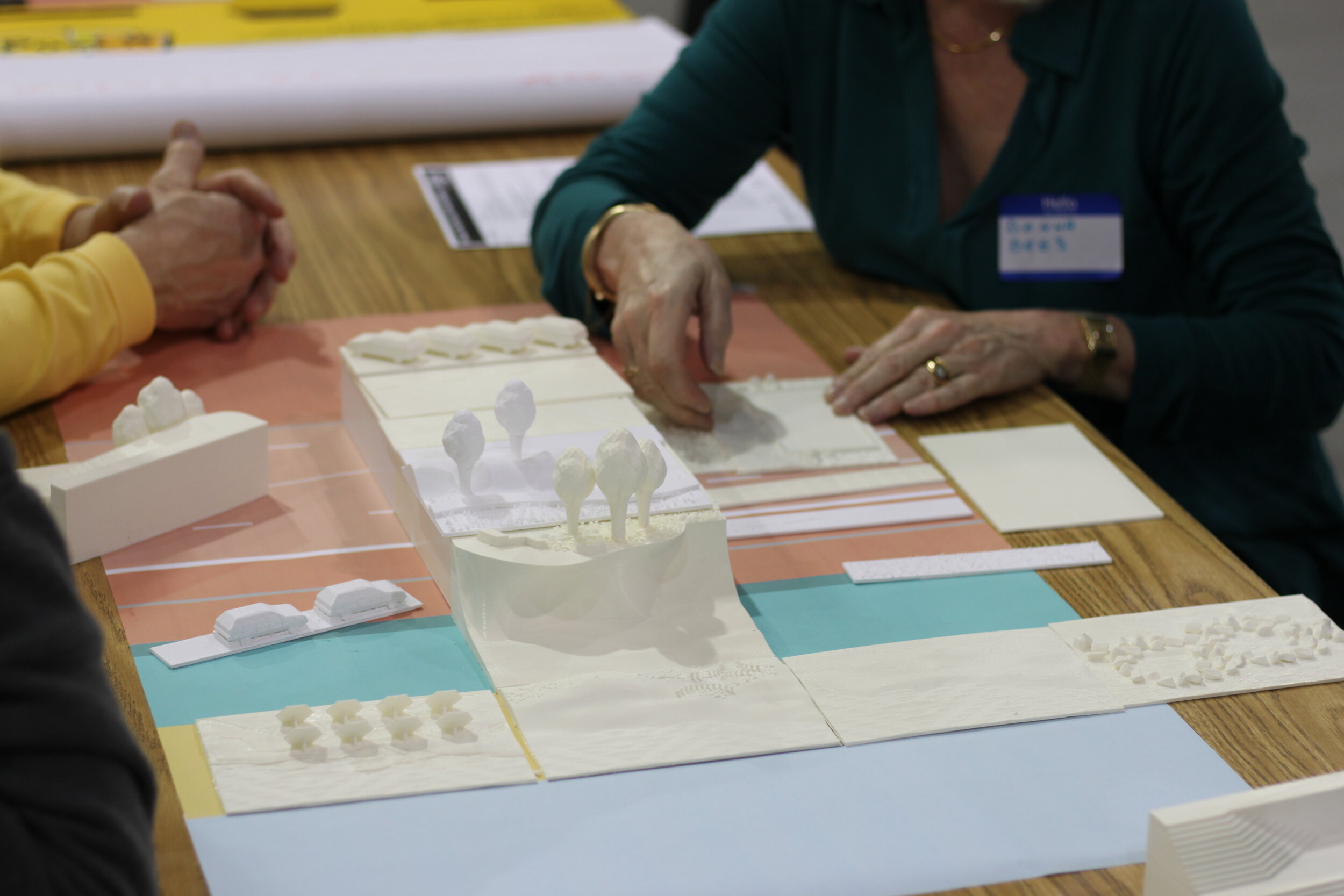

These are the tenets we employ when building teams at Stoss but there is one last component that we try to incorporate whenever possible… a social component. A happy hour or lunch before or after a meeting, a dinner to celebrate a project milestone, this helps bind us on a more personal level and helps bring down those invisible walls that can sometimes build up.

The process, especially in the case of complex projects, can be messy at times, taking unforeseen turns as new information is uncovered and new perspectives are brought to the table. But a structured approach to building teams, alongside a willingness to respectfully critique, reflect and iterate, allows for continuing, authentic and constructive input, all of which make any collaboration richer and more productive.